|

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

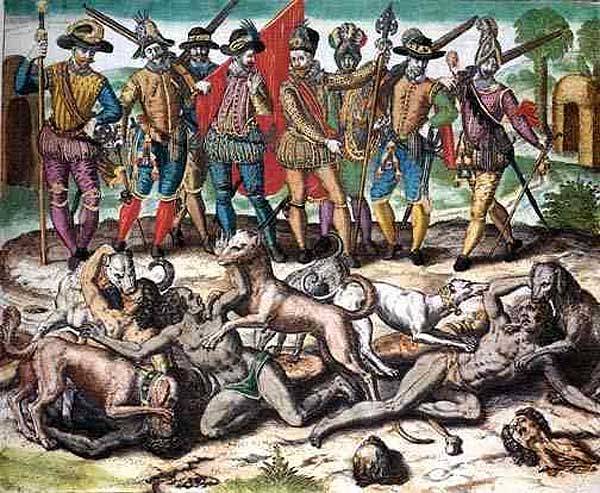

The Conquistador’s Dogs When Christopher Columbus discovered the Americas, he opened up a new era of political, military, and economic history. What most people do not know is that dogs played a vital role in the European conquest of the New World. Unfortunately it is also one of the most brutal chapters in man’s long association with dogs, so perhaps we have not so much forgotten this history as pushed it out of the collective memory. Although there are some gaps and lot of myths surrounding the life of Columbus, there is general agreement among most scholars that Cristoforo Colombo was born in Genoa, Italy, in 1451. His father was wool weaver and also involved in politics. He often took Christopher with him, and the boy quickly learned how to interact with people who had power and authority. Christopher and his brother, Bartolomeo, were educated together, learning to read and write in the craft guild school and then going on to study cartography, weather prediction, and basic navigation together. For a while Christopher was a clerk in a bookstore, a job that gave him a chance to read extensively about geography and the exploits of travelers who had visited Africa and the Orient. It also gave him a taste for travel, and the idea that there were many riches and rewards to be won in far-flung lands. Although in that era sons were generally expected to follow their father in the family business, times were changing. Genoa had been a major commercial center, treading in textiles, foods, gold, wood, ship supplies, some imported species, oriental luxury items, and above all sugar. However, there was considerable conflict throughout the Mediterranean region based upon religious lines, as Islamic and Christian powers fought for converts and territory. Constantinople fell under Muslim control when Columbus was only two years of age. With the resulting loss of the Aegean markets, Genoa adopted the modern-seeming solution of exporting knowledge. Soon cities like Lisbon, Seville, Barcelona, and Cadiz were importing a large number of Genoese marine experts, particularly seafarers and shipbuilders. In addition, Genoa was willing to supply merchants, bankers, and others with the financial expertise needed to make these new nautical enterprises successful. Thus it was not surprising when Columbus decided to look to the sea as a source of livelihood. He apparently worked as a common seaman for a while and then, as his navigational and cartographic abilities became apparent, rose in the ranks to become a junior officer. A turning point in his career seems to be his service on a privateer ship commissioned by Rene d’Anjou , the French pretender to the throne of Naples. This ship set out to make a surprise attack on a large Spanish galleon sailing off the coast of North Africa. All sailors on such expeditions were entitled to share of the booty, and as an officer, Columbus’s share was enough to give him the financial means to begin to pursue his own ambitions. He would still continue to sailing various capacities on other ships but would eventually rise to command a ship himself. During these years he continued to learn more about weather, ocean currents, and navigation, and he also became impresses with the exotic treasures that could be found in some remote places, that could be later sold for great profit. One of the great myths surrounding Columbus is that he was trying to prove that the world was round by sailing west and arriving in the Orient. This was not true, since the theory that earth was spherical in shape had been around since Greek and Roman times. It was then that the first cosmographers suggested there was only one large body of water and one large continent on the surface of Earth. On one shore of the great ocean was Europe, and on the far shore was Asia. If this theory was correct, than instead of the long and dangerous overland trip eastward from Europe to China, one could sail west to get to the Asian countries. What these early geographers could not agree upon where the distances involved. For instance, on Ptolemy’s map of the known world during Roman times, he drew the outline of the ocean surrounding the known lands, then marked the regions toward the middle as being “unnavigable” because the extent of the sea was supposedly unlimited. While Columbus was willing to accept the general outline of the world Ptolemy drew, he rejected the idea of an endless ocean. Chance would soon provide evidence to support his intuition. Columbus moved to Portugal because it was ruled by Prince Henry (later to be known as Prince Henry the Navigator). With Henry’s encouragement, the Portuguese had become active explorers and were conducting trade all along the African coast. While he was there, Columbus married Felipa Perestrello e Moniz, whose family belonged to Portuguese nobility. Although the family was relatively poor, they still had direct connections to the Portuguese court and the king, and Columbus used these to gain access to an important collection of papers. Once the property of the governor of one of the islands Portugal controlled in the Atlantic Ocean, the collection contained a treasure trove of information, including charts with details of ocean currents. It also held records of personal interviews with sailors described as found drifting in see currents from the west, suggesting that there were lands in that direction. Columbus began a correspondence with the aged cosmographer-physician Paolo del Pozzo Toscanelli of Florence, who concluded (in part based on the information provided by Columbus) that one could reach the Orient by sea if you sailed west only a little more than three thousand miles. Columbus was strongly motivated to explore to the west. There was a lot of glory and wealth to be gained not only by the person who opened up a quicker trade route to the Orient, but also by the nation that sponsored him. It was already known that Asia was a source of precious spices and rich textiles, and there were also tales of great stores of gold and jewels to be found there. Perhaps even more attractive was the possibility of achieving great power, since many believed that people who occupied these lands were not very advanced. Colonization by the presumably more sophisticated and technologically superior Europeans could provide cheap labor and perhaps ready and expendable foot soldiers to defend the homeland. Finally, there was the issue of religion. This was a time of religious tension, and Columbus was a devout Catholic. Pope Pius II had written extensively about the need to convert the heathen multitudes of the world to an understanding of Christ, with the continuing guidance (and control) of the church. Columbus’s faith was stirred by this, and it gave a new meaning to the knowledge that his given name Christopher, meant “Christ bearer”. He concluded that he was not only searching for wealth but also had a divine mission to accomplish. In 1500, Columbus would think back on his quest and write: “With a hand that could be felt, the Lord opened my mind to the fact that it [the voyage to west Asia] would be possible . . . and he opened my will to desire to accomplish the project . . . The Lord purposed that there should be something miraculous in this matter of the voyage to the Indies . . . God made me the messenger of the new heaven.” Columbus often noted that there were worlds in the Bible that were guiding him and may have been written for his own particular benefit, as a sort of prophesy. In particular he cited a passage in Isaiah (60:9): “for the island wait for me, and the ships of the see in the beginning: that may bring the sons from afar, their silver and their gold with them, to the name of the Lord thy God.” One could see how he would be attracted to this passage, since he viewed his own quest for far-off lands as a task done for both gold and God. Columbus’s first task was to find a royal sponsor. For an explorer in the fifteenth century, royal sponsorship was a necessity, since only a monarch could assert sovereignty, give legal legitimacy to the discoveries, and conduct diplomatic relations. A monarch was also needed if one were to colonize the land, since the new colony would have to be protected and defended, and laws had to be imposed to maintain order and oversee the exploitation of riches and the distribution of rewards. Private individuals, even those of wealth and power, such as prominent merchants or bankers would fall short of the resources to do this. To launch and sustain new explorations and discoveries, you needed not only an economic foundation, but also a strong political and military base. Columbus first sought royal patronage in Portugal, hoping to take advantage of his wife’s family connections and the Portuguese history of exploration in the tradition of Prince Henry the Navigator. The king passed Columbus’s proposal on to his Council of Geographical Affairs, who though that Columbus was underestimating the distances involved and overestimating the rewards to be won. Columbus then carried the proposal on to France, England, and finally Spain. Although the Spanish queen, Isabella, was interested in the idea of a west-ward crossing, she was preoccupied by a war with Muslims and the Castile region of the country. So she and King Ferdinand asked Columbus to present his Atlantic project to a committee of experts called to hear the case. The so-called wise Man of Salamanca reached the conclusion “that the claims and promises of Capitan Columbus are vain and worthy of rejection. . . . The Western Sea is infinite and unnavigable. The Antipodes [by witch were meant the lands on the other side of the earth toward which Columbus was to sail] are not livable, and his ideas are impracticable.” Columbus did not give up, however, and tried again in 1491. This time, events were more fortuitous. Ferdinand and Isabella had just wan the battle of Granada and had expelled the Muslims from Spain. With the return of relative peace to their country, they could attend to other matters. Without the draining costs of military actions, they allowed themselves to be convinced that the monarch could require the city of Palos to pay back a debt to the crown by providing two of the ships that were needed. In addiction, there was already an agreement in place providing Italian financial backing for part of the expenses. This meant that the crown had to put up very little money from the treasury. In September of 1492, Columbus set sail on what he felt was to be a trip to the Orient. Contrary to the myth that his crew was made up largely of convicts taken fro prison, in fact they were mostly experienced seamen recruited by the Pinzon brothers, who owned one of the ships and served as officers. There were a few government officials, but there were no priests, no soldiers, no settlers, and no dogs. This was a small-scale voyage of exploration and discovery, nothing more. The ships were quite tiny, no longer than tennis court, and less than thirty feet wide. Columbus, who was a tall man, could not even stand fully up-right in his little compartment. There were only ninety men – forty on the Santa Maria, twenty-six on the Pinta, and twenty-four on the Niña. The decks were crowded with supplies to last a year, and Columbus did not anticipate and need for dogs. Although the first voyage took a month, it was relatively uneventful. Landing at San Salvador, the Europeans saw people “as naked as their mother bore them” and many fruits and green trees. Columbus and his captains went ashore in an armed launch but were warmly greeted by the natives. When he unfurled the royal banner and declared that these obviously inhabited lands now belonged to the Catholic sovereigns, the natives’ appeared to offer no resistance to Spanish domination. In his own worlds, Columbus concluded “I recognized that they were people who would be better freed [from the bondage of their pagan religion and uncivilized lifestyle] and converted to our Holy Faith by love than by force.” He also encountered some native dogs in the New World; however, these did not bark and seamed only to be raised as food. Unimpressed, Columbus did not include them among the curiosities that he brought back to exhibit in Spain. When he explored Cuba and some of the other islands, Columbus encountered a few problems. The Santa Maria ran aground and was wrecked beyond repair. He considered that only a minor problem, however, since it provided him with lumber that he could use for building a front and also surplus crewmen to start a first colony. He left a small group of man with instructions to treat the natives well and not to “injure” the women. Their job there was to explore for gold, and to seek a place for a permanent settlement. He assured the local chief, Guacanagari that their intentions were peaceful, and then gave the new colony the name “La Navidad”. The second voyage started in 1493, and it would be quite different. It was massive, consisting of seventeen ships, twelve hundred man and boys (including sailors, soldiers, colonists, priests, officials, and gentlemen from the court), horses, and twenty dogs. The dogs were the idea of Don Juan Rodriguez de Fonseca, archdeacon of Seville and the personal chaplain to the king and queen. Don Juan had been put in charge of determining the supplies and equipment necessary for the voyage. In his mind, these mastiffs and greyhounds were classed as weapons, along with muskets and sabers. The Spanish military had recently learned to appreciate the effectiveness of dogs against men with little or no armor. When Spain took the Canary Islands away from Portugal, they were resisted by intelligent, brave and proud natives called Guanches, whom the Portuguese had never been able to subdue. The governor effectively used large war dogs to wreak havoc, resulting in the loss of many native lives. When the military saw how useful the dogs had been in that campaign, they decided to employ dogs in their struggle with the Moors of Granada. The lightly armored Muslim fighters were no mach for the mastiffs of that era, which could weigh 250 pounds and stand nearly three feet at the shoulder. Their massive jaws could crush bones even through leather armor. The greyhounds of that period, meanwhile, could be over one hundred pounds in weight and could stand thirty inches at the shoulder. These lighter dogs could outrun any man, and their slashing attack could easily disembowel a person in a matter of seconds. Several of the men who had served as dog masters at Grenada and helped to disperse the Moors would be among the crew of Columbus’s second voyage. Fonseca wanted dogs on this voyage because he anticipated difficulties ahead. Both the king and the queen indicated that they wanted kind treatment of the Indians and, of course, their speedy conversion to Christianity. The monarchs also wanted the land to be settled, communities and trade centers organized that these two aims were basically incompatible and some compromises would have to be made between the evangelical and the material aims of this voyage. To meet the royal expectation of large profits, the colonists would eventually have rely on enforced labor and perhaps even enslavement of the natives. Although the Indians might truly be as peaceful as Columbus described them, it seemed unlikely that the demands of this new regime for manual laborers would be readily accepted. Furthermore, the anticipated taking of resources and valuables, as well as the seizing of land, would likely need to be backed up by force. Since these natives had no armor and only light weapons, dogs would be a formidable form of coercion. The twenty dogs that Columbus took with him, and the others that followed, would eventually blaze a bloody trial across the New World. One of the first things that Columbus did upon his return to the Americas was to go to the site of the colony that he had established. All of the personnel on the ships were eager to land; they wanted to start looking for gold and building new settlements. As they approached La Navidad, they fired a cannon to announce their arrival. However, there was no response – no one returned the salute, and no flags were waved. As the site came into view, the voyagers were horrified to discover that the entire population of La Navidad had been massacred, and the fort had been burned to ground. When they searched for traces of their countrymen, they discovered a mass grave in which several Spaniards had been buried. They also found that the village of Columbus’s good friend, Chief Guacanagari, had been destroyed. Although the full details of what happened may never be known, stories told around the countryside were that the settlers had become greedy, making demands for valuables and food. In addition, they had raped some Indian women and acted cruelly toward other natives. In response Indian razed the settlement. More importantly, they became hostile toward Europeans and began to spread the word among the other tribes. It was becoming clear that Fonseca was right about the need for dogs. The very firs military conflict between Indians and Europeans would also mark the first incident where a dog served a military purpose in the New World. In May 1494, Columbus approached the shore of Jamaica at what would become Puerto Bueno. He could see a gathering of natives, painted in various colors and carrying weapons the fleet needed wood and water, and Columbus was still angry and looking for revenge for the destruction of La Navidad. He also felt that perhaps a demonstration of Spanish military strength might just frighten the natives enough to cause them to avoid any further hostilities. Three ships approached to shore. Soldiers fired their crossbows and then waded ashore, slashing at the natives with their swords while others continued to fire bolts. The Indians were surprised at the ferocity of the onslaught; however, when one of the of the massive war dogs was released their response was absolute terror. They fled from the raging animal that bit at their naked skin and did them a great harm. The admiral then came ashore and claimed the island in the name of Spanish throne. Columbus would write in his journal that this incident proved one dog was that estimate to say one dog was worth fifty men in such combat. The pattern for conquest had now been set. Weapons would be used to actually take and hold territory, while dogs would be used to worry and terrify the natives. Thus when Columbus took an expedition into the interior of Hispaniola (the island in the West Indies that contains both Haiti and the Dominican Republic), he met any show of resistance by unleashing his dogs and allowing them to pursue Indians. The dogs killed many of the natives, and those who survived to be captured were sent to the slave market in Seville. Among those held at bay by the dogs until they were captured by the Spanish soldiers was an Indian chief Guatiguana and two of his companions. Scheduled to be hanged the following morning, they managed to gnaw through the thongs used to bin them, and escaped. Guatiguana was now bent on eliminating all of Spaniards in his territory, and he began to organize a large-scale resistance. First the Indians tried to weaken the invaders by planting no more maize and removing all of their livestock from the region. Columbus, angered by the starvation tactics and the gathering of hostile force, decided to act before the chief could mount an attack. Because many of his men were ill and weakened by the shortage of food, he could only muster a force of around two hundred soldiers, but they were supported by twenty vicious and well-trained dogs. What would be the first pitched battle between the European invaders and the native Indian population took place at Vega Real in March 1495. Guatiguana’s forces, numbering in the thousands, advanced upon the small band of Spaniards. Columbus had given control of the dogs to Alonso de Ojeda, a small man who combined physical courage with a personality disposed toward violence and rash cruelty. He justified his often gruesome behavior by citing the fact that he was citing to honor the Holy Virgin and always had small portrait of her with him. Ojeda had learned the art of using war dogs in the battles against the Moors of Granada. He gathered the dogs on the far right flank and waited until the battle had reached a high level of fury. He then released all twenty mastiffs, shouting “Tómalos!” (meaning “take them” or “sic ’em”). The angry dogs swept down on the native fighters in a raging phalanx, hurling themselves at the Indian naked bodies. They grabbed their opponents by their bellies and throats. As the stunned Indians fell to the ground, the dogs disemboweled them and ripped to pieces. Spinning from one bloody victim to another, the dogs tore through the native ranks. One observer of the battle, Bartolome de las Casas, reported that in less then one hour each dog had torn apart at least one hundred Indians. Recognizing that his readers might find this difficult to believe, de las Casas explained that these animals had originally been trained to hunt for wild game. In comparison, they found that the skin of their naked human opponents was far easier to tear apart than the hides of deer or boars. Furthermore, as Fonseca had surely anticipated, the dogs had now developed a taste for human flesh. The battle of Vega Real awoke Columbus to the potential that his dogs had as weapons against the inhabitant of this new land. He would work his way through the countryside, now always accompanied by his dogs. Ultimately he would bring all of the tribal leaders in Hispaniola under his control through the threat of force and the use of his dogs to inspire fear. Each subsequent voyage to Americas would bring more dogs, and ultimately virtually all of the leaders of the conquistadors would employ them as fearsome weapons. Familiar names, like Ponce de León, Balboa, Velasquez, Cortes, De Soto, Toledo, Coronado and Pizarro, all used dogs as instruments of subjugation. The dogs were encouraged to develop a taste for Indian flesh by being allowed to feed on their victims. Soon the dogs became very proficient in tracking Indians and could tell the difference between a trial made by a European and that made by a native. The cruelest of Spanish leaders would use the dogs as a means of public execution. Known as “dogging” it involved setting the dogs on the chiefs or other high-ranking individuals in the various tribes. Watching their leaders being torn to shreds instilled great fear in the native population, who would ultimately submit to Spanish control rather then risk such a horrific death. The cruelty of the conquest eventually brought out a sadistic streak in many of the soldiers. Some would release the dogs on Indians simply for the sport of watching the natives suffer and die. Sometimes they would bet on the outcome, such as where the dog would draw blood first, how or where the fatal wound would be dealt, or how long it would take for victim to die. Although word of such barbaric behavior was brought back to Spain, little was done to stop it. While these dogs were considered to be mere weapons and sometimes instruments of torture, some of them became famous as individuals, and their names have been preserved in the histories of the time. There was Amigo, the dog of Nuño Beltran de Guzman, who played a pivotal role in the conquest of Mexico. Bruto, the dog of Hernando De Soto, was a vital factor in the takeover of Florida. In fact, when Bruto died, his death was kept secret because the simple motion of his name was capable of striking terror into the natives and causing them to submit immediately. There was also Becerillo, the dog of Juan Ponce de León, and the dog’s son, Leoncico (the name means “little lion”), who belonged to Vasco Nunez de Balboa. Leoncico would evaluate each situation and respond accordingly. When he was sent to apprehend a native, he would race out and grab the man’s arm in his mouth. If the Indian did not struggle, but came along, he would be lead safely back to Balboa. If the Indian resisted, he would be killed and torn apart immediately. Leoncico was considered to be so valuable that he was awarded the rank of a caporal, including pay and entitlement to share any goods or gold obtained as booty. When one considers the bloody history of dogs during the conquest of the Americas, there is almost an automatic emotional response. One feels ashamed of the behavior of the dogs, and wonders how we could ever consider these vicious creatures to be our friends and companions. However, it is important to remember that dogs are born with courage, intelligence, and a sense of loyalty – not with a code of morality. Their human masters trained them their own concept of right and wrong into these dogs; in the hands of hardened soldiers, they were changed into lethal weapons. Remember that in a murder trial it is not the weapon used to kill but the individual wielding the weapon who is called to justice. The conquistadors who ordered the dogs were merely responding out of a sense of loyalty, and their actions were performed with courage. Despite the cruelty of the time, there was one incident in with a dog caused the invaders to question the morality of their actions, at least for a short time. This involved Becerrillo, the dog of Juan Ponce de León. He was a large dog (his name means “little bull calf”), who also looked quite fearsome due to his scars from many battles. Since Ponce de León had many duties as governor of Puerto Rico, the dog was often entrusted to Capitan Diego de Salzar, an intimidating and ruthless man who was often deliberately employed to strike quently the instrument used to create that terror. Salzar often ordered Becerrillo to tear apart Indians who showed any defiance to their conquerors, and this was done publicly as an object lesson to others in the community. In battle, this dog was devastating. For example, when the natives decided to band together to kill all of the Christians, they sent a chief, Guarionex, to lead a surprise attack against the village where Salzar and his troops were staying. In the middle of the night, the raiders began setting the straw-thatched huts on fire. Becerrillo began to bark frantically, waking the troops. Salzar leaped out of bed with a shout, and naked except for his sword and shield, he rushed into battle with Becerrillo at his side. The clubs and darts of the Indians were no match for Becerrillo’s teeth. Although the battle only raged for about a half hour, at the end even the Spaniards were surprised to find that the casualties included thirty-three natives killed by Becerrillo’s savage fangs. Over the next several months, Salzar and Becerrillo went in pursuit of Guarionex and the other surviving raiders. The Indians came to fear this beast to the extent that they would more readily stand and fight a hundred Christians without him than ten with him. On one particular occasion, not far from Ponce de León’s capitol at Caparra, Salzar and Becarrillo had just broken the resistance of group of natives. When the struggle was over, the troops had nothing to do while they waited for the arrival of the governor, who was expected in few hours. Salzar decided to relieve the tedium with a bit brutal entertainment. Calling over an old Indian woman, he gave her a piece of folded paper and told her to carry the message down the road to the governor. She was told that if she did not do this, she would be cast to the dogs. The old woman was frightened, but also hopeful that perhaps this errand might somehow lead to some freedom and respite for her people. She had not gone far toward the road when Salzar laughed and unleashed Becerrillo with the attack command, “Tómala!” (take her). The great dog dashed toward her as expected, and the amused soldiers waited for Becerrillo to tear her to pieces and then gorge himself on her flesh, as he had done with so many other Indians before. The unfortunate woman saw the huge dog rushing toward her with his fangs bared. She dropped to her knees and cast her eyes down and than softly, in her own language, uttered a humble plea. “Please, my Lord Dog,” observers heard her say “I am on my way to take this letter to Christians. I beg you, my Lord Dog, please do not hurt me.” Who knows what went through the mind of Becerrillo. Those who saw the event claimed that the dog displayed almost human intelligence and compassion. Perhaps it is the fact that the woman had assumed such a humble and non-threatening posture, or perhaps it was the soft tones of her quiet qords that soothed the dog and demonstrated that she was not hostile. He stared at the woman’s face as she gingerly held the sheet of paper with both hands in front of her chest – to show him that what she said was true, or maybe to hide behind it as if it were a shield. Becerrillo sniffed at her, nudging her with nose, and then sniffed at her hands and the paper. This fearless killer then turned away from terrified woman, lifted a leg, and sprayed urine at her. He then walked to the side and watched as she shakily rose to return to the soldiers who had planned to have her killed. Since Salzar and the assembled troops knew Becerrillo so well, and had so often seen him with his mouth dripping from the blood of his victims, this seemed like an impossible outcome. In their minds this only could have come about through some from of divine intervention. The vicious pranksters had been put to shame by the charity and mercy of a hound. Doubtless they felt humiliated by this incident. A short time later, Ponce de León arrived and was told the story. The governor shook his head in astonishment. “Free her,” he commanded, “and send her safely back to her people. Then let us leave this place for now. I will not permit the compassion and forgiveness of a dog to outshine that of a true Christian.” send by: Ewa Ziemska

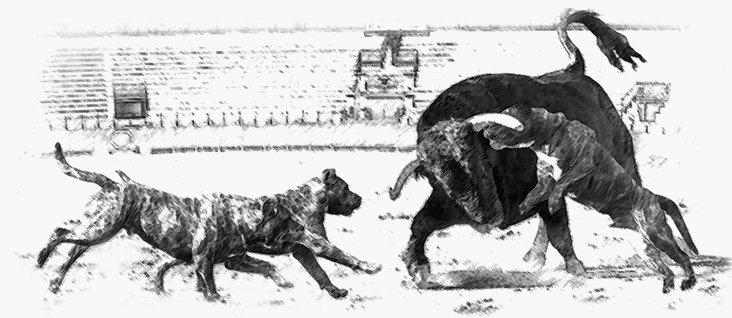

Dogs releast by Pizarro - people from Peru atacked by dogs of Balboa

|

||||

|

|

||||